FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Dee Dee DeBartlo

deedee@debartlo.com / 212.365.8766

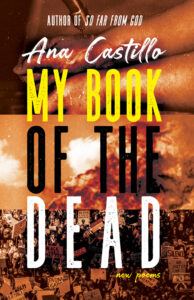

MY BOOK OF THE DEAD: New Poems

By Ana Castillo

In MY BOOK OF THE DEAD: New Poems Ana Castillo, called “the most daring and experimental of Latino novelists,” surveys the America landscape – its killing fields littered with the debris of our excesses, ghosts haunting its dark contours – and speaks to us in verse, English and Spanish, of the destruction we’ve sown with selfishness, greed and animus for those we’ve othered.

Castillo is a scholar, a renegade, a survivor, a first generation American, a daughter of Mexican immigrants, an activist who came of age in Chicago in the 1960s. She is also a creative powerhouse and public intellectual renowned for pioneering feminist analysis in non-fiction and fiction. And while she is most recognized for her prose and essays, poetry has always been her first love.

And here she is, a poet at the height of her powers, looking back and looking forward in poems that are at once highly innovative and based on established oral and literary traditions. These are poems personal, historical, political and emotionally combustible.

A book of forty-eight deeply imaginative poems written in three parts, here on the page is our country in the Twenty-first century: the pandemic, the deaths, the lies, rampant inequality, unbridled consumption, mass shootings, boundless anxiety all on a warming planet.

There are several poems in Spanish with glorious translations into English (by the poet and with translators). There are persona poems to break your heart: the voice of a Bedouin woman whose beloved son, a writer, is in prison; a poem about death by gun called “Incomplete List” that catalogues race murders, suicides and school shootings – the locations, dates and people gone. And other poems of remembrance, “Akilah and me, tokens . . . brown female evolved spirit/from the Southwest or southside of any city.”

There are poems about the predation of the Earth; a shut-down of the whole Federal Government; of motherhood, love, friendship and getting old. Here’s musing on Art: “Today anyone may have instant fame./But the number of geniuses is the same/any given time./Maybe five.”

There’s a sly homage to Bukowski and Bolaño in a poem titled “Two men and Me” and a pastoral poem about Whitman.

MY BOOK OF THE DEAD paints a vivid panorama, a contemporary Hieronymus Bosch triptych in breathtaking magnificence because of Castillo’s skill, her ear, her vision, and her courage. Infused with passion, lyricism, and magical realism, Castillo makes us laugh and cry and speaks truth we need to hear.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

selfie on Palm Sunday, 2021

Ana Castillo is a celebrated author of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and drama. Among her award winning books are So Far from God: A Novel; The Mixquiahuala Letters; Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me; The Guardians: A Novel; Peel My Love Like an Onion: A Novel; Sapogonia; and Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma. Born and raised in Chicago, Castillo resides in southern New Mexico.

ABOUT THE BOOK

MY BOOK OF THE DEAD: New Poems by Ana Castillo

Published by University of New Mexico Press

On Sale September 1, 2021

$24.95 Hardcover / 144 pages / 14 drawings

978-0-8263-6319-0

Past interviews

Sep 3, 2014

“We write what we know, and this is what we do know,” says Ana Castillo — novelist, essayist, poet, teacher, truth-teller, and, as she has come to be known, one of the first generation of highly visible Chicana writers.

“They describe us as ‘Chicana writers, in search of their identities.’ We’re not looking for identities — we have this identity,” adds Castillo during our conversation at an independent bookstore in Chicago, her hometown and a stop on her author tour to promote her newest novel, Give it To Me (2014, The Feminist Press) (http://www.anacastillo.com/content/).

Give It to Me is Castillo’s sixth novel, written in only two months, a testament to her mastery and a successful journey from her first novel that she spent “so many years learning how to write.” In college, Castillo’s plan had been to teach art in high school, but she veered from that more conventional path to become a self-taught poet and then a self-taught everything else literary, now with two New York Times Notable Books of the Year to her credit. Today, she is called one of the most powerful voices in contemporary Chicana literature.

When Castillo moved to California after college in the 1970s, the era of Cesar Chavez, she encountered “Chicana,” which was “a big word” then used in academia. “Coming from Chicago, I saw myself as Mexican-American. But I was born here,” she adds. By the time Castillo returned to Chicago, she proudly brought the Chicana label with her.

“It bothers me that the various powers that be still see me as a label and decide whether that is the flavor they want or don’t want,” Castillo says. But after numerous volumes of fiction, poetry, and essays, she clearly isn’t hampered by a label.

Little wonder then, at the reading and book signing for Give It To Me, a young woman in the audience tells her, “I see you as a role model.”

Little wonder then, at the reading and book signing for Give It To Me, a young woman in the audience tells her, “I see you as a role model.”

In slim jeans and a lace-trimmed top accessorized by bold silver jewelry (a silversmith has launched the Ana Castillo Collection), the author is clearly comfortable with herself, which makes her a role model for everyone. She celebrates her identity and wields her considerable creative power to give it a voice.

With her long black hair and dark eyes, Castillo wears chili pepper red lipstick — the same shade her mother wore. “My mother used to get up at four in the morning and take three buses to the factory where she worked, but she always wore that red lipstick.” Here is a powerful heritage of women — hard-working, often oppressed, and scraping together a better life for themselves — who could still “put on that red lipstick like Queen Nefertiti.”

Castillo creates characters who survive and thrive, in spite of it all, such as the Give It To Me 40-something protagonist Palma Piedras, who divides her time between Chicago and New Mexico, with a detour to L.A. in the company of two hustlers. The novel is one-half sexual adventure, and one-half poignant search for love and meaning that are always found within. Palma is feisty and uninhibited, and unblinkingly realistic about herself and the world. My favorite line about Palma and her complicated love-interest cousin: “They weren’t just family but cut from the same brutal cloth of inequities. Life wasn’t fair and they made it work.”

That attitude raises survival to an art form.

Castillo, who has been “coming back” from breast cancer in 2008-2010, knows about surviving. Writing has been her way of making sense of what life dishes out since age nine, when she started composing poetry to deal with the death of her grandmother who had been her primary caregiver. Throughout her career, Castillo expanded genres to reach bigger audiences. “Everybody writes poetry. Few read poetry, and nobody buys poetry. So I began putting my stories in fiction,” she says.

Her writing is populated by women who differ from the feminine archetypes in literature—Alice in Wonderland or Little Women — who “were not anything like the women I knew or the girl I was.” Rather, Castillo writes about “beautiful brown women — and by beautiful, I don’t mean an aquiline nose or tall and blond. Strong, resourceful, capable of making the best of it.”

Indeed, Castillo writes what she knows — and lives.

‘Write What’s Tearing at Your Heart’: Feminist Ana Castillo on Writing Her Rape

‘Write What’s Tearing at Your Heart’: Feminist Ana Castillo on Writing Her RapeIn her new memoir “Black Dove,” poet, novelist, and academic Ana Castillo delves into deeply personal topics, including her son’s incarceration, the discrimination she faced within the feminist community, and her sexual assault.

By Ilana Masad

May 10, 2016

An alternative term for Chicana feminism, the word Xicanisma was coined in 1994 by the Mexican–American poet, novelist, playwright, translator, essayist, and scholar Ana Castillo. An activist throughout the 70s and 80s, Castillo had grown disenchanted with the white feminist status quo and wanted to offer a way for Latinas to see themselves in the women’s liberation movement. And although Chicana feminism had recently been picked up and dissected by the academy, Castillo felt it had “fallen prey to theoretical abstractions”; she wanted to reclaim Chicana feminism and “carry it out to our work place, social gatherings, kitchens, bedrooms, and society in general.”

Since then, Castillo has published several novels and poetry collections, taught memoir and nonfiction writing classes, and been awarded the LAMBDA Foundation’s award for Best Bisexual Fiction. Nevertheless, even for the radical feminist known for crossing boundaries, her new memoir/essay collection, Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me, out this week from the Feminist Press, represents something of a departure. Castillo’s essays range from stories about her grandparents—Mexicans who came to the US only to be deported during the Great Depression—to her parents’ and aunts’ histories, to narratives about herself. She writes about puberty, her romantic relationship with a well-known feminist (whom she never names), and, perhaps most poignantly, her only son’s incarceration and recovery from addiction. She also touches on subjects she’s never discussed before, such as her experiences with sexual assault. We talked to Castillo about the process of getting so personal after a long writing career.

BROADLY: Why did you choose the title Black Dove?

Ana Castillo: “Black Dove” [“Paloma Negra“] is a mariachi song, and we Mexicans love our mariachis; we’d go celebrate Mother’s Day or a birthday or something and ask for a song that brings a great deal of sentimental feeling to us individually or the table. That’s how I feel with “Black Dove.” In the book I explain that it’s a song that my mother actually sang as I left home as a young woman. My mother was very traditional, and in her mind, the way a girl leaves home is through marriage—me going out with my little satchel was not how they imagined it. They imagined the worst, that I was going to end up in a cabaret as one of those that dances for a few fellas.

But then of course as time goes on I became a mother of a son, and he was also out and about. In his teenage years in Chicago he was picked up by police for jumping trains and graffiti tagging. By day a good boy, in the International Baccalaureate program, and playing cello in his school, and by night having this other life. He became my black dove.

You write about the two years your son spent in prison for theft, and about his journey to sobriety. How does he feel about this book coming out with his image and his pen name in it?

He doesn’t seem to be worried at all, because this is part of the process of moving on. It’s also part of the process of social change, bringing out these subjects and talking about them. I did a reading and signing at Women and Children’s Bookstore [in Chicago] for National Indie Bookstore Day, and both he and my granddaughter signed copies for people with me. Unlike me, he’s quite a talker, and people were very supportive. He does not at all deny his mistakes. He paid his dues, and he is now working at a not-for-profit and helps a lot of people who are in transition [from the prison system]. He is studying for the LSAT exam. He’s corrected his life, and he’s an awesome dad.

The issue of mass incarceration, the multi-billion-dollar industry that prisons have become in this country, is important to talk about. The fact is that young people of color are being harassed as much as my generation was 30 years ago despite the civil rights movement and all the other ways that we’ve brought up race issues in this country. His imprisonment was one of the most painful experiences I ever went through in my entire life—and I went through breast cancer. Even cancer didn’t come close to how painful it was to see my son going through such depression and so much pain, so much anguish, that it made him press an eject button and get out of society all together. We pushed through that.

What was it like for your son when he came out of prison?

He was not able to rent on his own initially. He immediately went to a paralegal program and went through it, and then he couldn’t get hired because of background checks. So for a year after he was released, he worked as a food runner. Now he has a nice apartment and his landlady knows his background and is very encouraging of him and he’s got a good job—they [also] know his background—and he’s also helping a lot of people, but it came with a couple of years of pushing.

I can only imagine those unfortunate people who get arrested just for selling weed or carrying it, who come out and have young families and they can’t rent an apartment for their children, for their family. They can’t even get a job as a food runner or waiter. Is this really what we want to do? Punish people after they’ve been in prison and not allow them to assimilate [back] into society? All of those are reasons why it was really critical for me to put it out there in the book.

Identity plays a crucial role in the essays. Do you deal with identity a lot in your daily life as a writer?

I think that very few people in our world have the luxury to not think about it. Today in 2016, if you’re white or if you can pass for white, you might not be thinking about how your life is affected by your color. In my case, I’m immediately reminded that I don’t look white, that I don’t look… we may say American. So I do have to think about that. As a woman, too: What are people perceiving [about] me as a woman? As I got older, into middle age, I also began to be treated differently both in public and in the different spheres I move around in because there’s the question of ageism. Women begin to lose some of their cache in the public eye; it starts to happen around 30. It’s shocking the first time someone calls you ma’am.

More and more I’ve been really disrespected in many public spaces, by strangers. It’s very telling of the world we live in. I don’t think I look like a purse-snatcher. I think I go out in the world well-groomed. Yet I can’t tell you how many times white women will pull their purses close to them when they see me approaching. It’s so common, it’s like a tick. I haven’t said anything to them ever, but it bothers me to see it.

Do you feel that same casual discrimination in the publishing industry? Do you feel like you’re being boxed into a place of representing a minority voice against your will?

We were at ground zero when I first started writing: US Latinas were not published. Even Latin American women in translation were rarely published. I’ve published with numerous big publishers in this country and the world. I’ve left them, ultimately, because even though I had a name and a reputation and proved to have staying power and a substantial following and my books are taught in universities, there was a sense that a certain kind of safe writing was desired of me. I take every risk in writing that I can, because I don’t write just to entertain people or make money. You have to be a risk taker to publish me. In the last five years, I left the latest major publisher I was with and found a home with the Feminist Press, which has been supportive of women’s writing and women’s rights around the world. It’s so great to be with a publisher that gets you—they get it. Though they might not have the financial resources to put me on Good Morning America, they are behind me.

Is this the first time you’ve written about your suicide attempt and your rape?

Yes, it is. I may have shared a couple of those things with my very best friend over the years, but I never thought that I would ever write about it. But I teach memoir writing: I always tell people that you have to write what’s tearing at your heart, what you need to resolve. I thought it was time to walk my talk. How was I going to write about parts of my life and not write about what really was motivating some of my behavior? I’ve written long enough to know where the boundaries are.

What about your relationship with the woman you don’t name? Do you identify as queer or bisexual?

In breaking up with my out lesbian girlfriend—who is a public writer and does identify as a lesbian, and it’s a big part of her career—there was a great stigma. This was the 1980s, and this idea of being “back in the closet” followed me into the 90s. I heard that many, many times in my professional life, that I had gone “back into the closet” because I was no longer talking about it in public.

So you were discriminated against by your own feminist and progressive communities at the time?

Yes. There was no bi community, and I think all bi people were being discriminated against. [The attitude was,] “Okay, so you were gay, and now you’re not gay. You went in the closet and you betrayed the lesbian cause.” That wasn’t true. Before I met this woman, I was married to a man. After she and I broke up, I was married briefly to a man, but I have also had relationships with women—women who were not necessarily out because they were professionals in a world that’s very hostile to women to begin with, but also with women who lead nonconformist lives. It might have been obvious that they were with me, but we wouldn’t put it out there for the media.

For most of my adult life I have been single. I have lived alone; I raised my son alone. For a long time, years and years, he and I were in the same household alone. There wasn’t really a subject that I had to address. “Oh, by the way, I’m bisexual. I’ve been alone for five years, in case anybody’s interested.”

In one of your essays in the book, from 2012, you write about Beyoncé and Jennifer Lopez and say they are “[d]oing no more than supporting and promoting patriarchal and capitalist goals.” Do you still feel this way about them, even as they—Beyoncé especially—are often held up as feminist icons?

Buy directly @ UNMP or from your fave bookseller

I do, but I know that I would have a lot of women of color of younger generations argue with me about that. I come from a generation of radical feminism; we believed in not using your body for financial gain and that sexualization fed into violence against women. I know that dates me. The performances that both Jennifer Lopez and Beyoncé give are highly sexually charged, and they’ve made a lot of money off of a lot of men by sexualizing themselves as exotic beauties. Both of them have dyed their hair blonde, straightened it, weaved it, which feeds into a fantasy about women and women of color.

I come from a very different perspective, and I don’t believe that anything in terms of personal gain or materialism is really helping the rest of the world. If you make that much money, instead of buying a humongous mansion, go back to your community and start community projects and talk to your legislators about changing some of the laws [that mean] young men of color who have felonies because [they dealt] drugs as teenagers can no longer integrate into society. Moving away from Beyoncé and J-Lo—I’m sure they do a lot of good deeds—I’m very lucky I have a roof over my head. I can eat healthy food, my children have coats in cold weather, they have an education. I don’t think a human being needs much more beyond that.