Rudolfo Anaya se nos fue al cielo

It’s a bitter sweet honor to launch the new La Tolteca 2.0 here with a tribute to Rudolfo Anaya. We mourn the loss of one of the first self-identified Chicano writers and champion of our literature and many other writers.

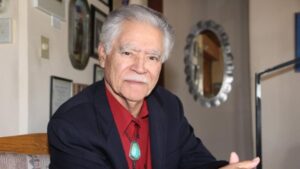

Rudy, as those of us who knew and loved him knew him, lived his life on his ancestral land of New Mexico. He taught at one university, UNM-Albuqueque. He married one woman until she passed, Pat Anaya. He had no children of his own but with Pat helped raise a granddaughter. You could say Rudy was a stable man, loyal to his people, family and to the literature he began to write, read and teach in the last 60s.

He reached out to me with my first book, WOMEN ARE NOT ROSES and included one of my stories in an anthology he edited. In time, we became friends. The last time my son and I saw him was a morning visit to his home (the home he built with Pat and the only one I know they called home.). Marcelo recalls Rudy insisted we do tequila shots, that I bought pan dulce and the tamales he had a lady friend re-heat for us before we hit the road. The last time I heard from him was via two hand written letters I received about six months ago. He had read my last book, BLACK DOVE. In the letter he said he believed the book should be used in every classroom throughout the country.

Rudy was like that, Chicano til the end. He left this life at 82, I suspect he couldn’t wait anymore to join Pat. She was a white woman, originally from Kansas I seem to recall and who devoted herself to him throughout their marriage. She edited his books. She kept their house. She traveled with I’m to almost all his gigs and certainly the most prestigious.

We have so many memories of Rudy–readings in this country together in Albuquerque but also in D.C. and Mexico. We have family memories at home. He got to know my mother. He was amazed to see Mi’jo grow to tower him. He preceded the Baby Boomer generation, led the way for us to have pride in our Chicano identities–too diminished, neglected, even despised by ‘gringos,’ as he called Whites.

For those who want to toast to a New Mexican son, teacher, mentor, leader and supporter of Chicano literature, American literature and an example of how to make your life as a writer (write and keep trying. Find a day job to pay your bills. Read others, read those who came before you and those coming up on your heels.) his drink was tequila on the rocks.

We toast to you, amigo nuestro. Remember us in heaven who share the torch you’ve passed on to carry on.

I include here an essay we ran in the first La Tolteca ‘Zine (issuu.com). It was a review and tribute to the Padrino of Chicano lit by mi’jo. My son is an example here of how important it is to teach our children to respect, learn and benefit from what our elders how gone through. We will miss Rudy, Rudolfo Anaya, Anaya in our small and extended families. C/S.

Going Home: A Tale about Love, Identity and What it Means to be a New Mexicano in The Southwest

Reviewed by Marcelo Castillo

Don Rodolfo Anaya has outdone himself once again with his nuevo young adult novel, Randy Lopez Goes Home. At first glance, Randy Lopez is a coming-of-age cuento de un joven who has traveled out into the World de Los Gringos to live amongst them, to learn from them, to enlighten himself in their ways and then returns to his small village Agua Bendita (or en inglés Holy Water, the home of his ancestors), nestled in the mountains of northern Nuevo Mejico with the directed purpose of reuniting with his one true love, Sofia of the Lambs. “Go and learn all you can, Sofia has told Randy, “I’ll wait for you under the cherry tree.”

However, in “A Note to The Reader: How Randy Lopez Came to Me” included at the edition, Anaya informs us that his wife Patricia “was dying, as Randy dies in the story.” What young readers and all readers then find is that the protagonist finding apurpose in ‘the hereafter.” What started as a simple, yet beautifully rendered coming-of-age story about true love becomes is an allegory. Randy Lopez Goes Home is a tale about a young man who goes to heaven to reconcile his past. According the Anaya it served the author to grieve the passing of his soulmate. Randy Lopez is a celebration of their final collaboration and Anaya’s mastermind has invited everyone to una fiesta that includes the seven vices, the four horsemen of the Apocalypse, La Llorona. Grendel, Tiresias the Soothsayer, Greek heroes and don Quixote and even his sidekick, Sancho Panza.

There are many themes at play, to be sure, from songs about nature, dreams, true love, Anaya’s own philosophies on life and death, preserving cultural traditions, time itself, personal memory and God. At the heart of Randy Lopez Goes Home is the exploration of the main character’s Chicano. A young Chicano reader might ask: did Randy make the right decision by going to Gringolandia? Or, how did he get the gringo nombre Randy, anyway? And specifically, for the sake of the book’s ‘message,’ did Randy changed by leaving the ways of his ancestors? What Anaya has done, besides write another bone fide Chicano epic, is to create a story that brings the Chicano Movement up to the 21st Century.

The story’s hero tells of working in a bookstore and how times were changing. Books were now electronic and the world itself, seemed to be becoming virtual. Later on, a curandera named Única (an updated version Última in Anaya’s most popular book, Bless Me, Última), wakes Randy up from a dream within a dream and explains the importance of “deleting the dream within the dream,” like he would delete a file on his computer. In other words, Anaya acknowledges the effect that modern technologies have on Chicano art. This conversation with Única causes Randy to reflect on his lost book, ‘My Life Among The Gringos,’ a theme recurrent throughout the novel. Randy wrote the manuscropt on a used laptop he paid for by working as a gardener for ricos and lost it when the express train he was riding to Sante Fe to show a potential publisher hit a cow. The characer had the chance to save his laptop or his trusty dachshund, Oso. Good choice, judging by Oso’s loyalty later in the book and the Chicano dog’s sense of humor (Even Randy’s perrito speaks Spanglish!

Regardng identity, Anaya writes “¿Un Pocho?” and “Chicano?” when asked what he is to los mejicanos that help Randy build his bridge to Sofia, his true love, goddess of widsom. Despite their simplicity of style these literary subtleties are thought provoking. Along with using the traditional spelling mejicano, Anaya teaches us that there are new as well as classic ways to perceive Chicano identity. Anaya, el Profe, is on an eternal mission to teach us through his writing what is possible for aspiring Chicano writers if they are able to reconcile their mixed heritages and cultural backgrounds. Through Randy, Anaya explores the plentitude of Chicano concepts: Indo-Hispanos, Spanish Americans, Mexican Americans, Hispanos, Chicano, Latino, and even the old derogatory names of Greaser and Wetback. Randy reflects on what it means for a nuevo mejicano to be un Americano today. Where did the word gringo come from, anyway? Randy asks. There were other labels for them tambien: bolillos, güeros, gringos salados, y gabachos. After having a deep conversation with his godfather about the indio blood coursing through his veins, Randy concludes that “the time of the mestizo had arrived!” and that “maybe” the two cultures, gringo y mestizo, may eventually mix together. The fact is, mestizo blood has mixed for over five hundred years and but it is Randy’s personal discovery here that seems to be the author’s intention.

In the story, the protagonist also ponders what it means to be “Anglicized.” New Mexico became a state a mere century ago. Gringos, preceded by Spaniards or ‘gachupines,’ as they were often called, were there long before. Miscegenation occurred on that land, even in the rural areas of a place like Agua Bendita. The term Anglo is generalized used for Whites in the Southwest Randy wonders, however, how so many brown Chicanos could give up their skin color? Admitting to himself that there were indeed light-skinned Chicanos, he decides that “culture was more than skin.” Cultura was “Language. History. Legends. Music.” We see Randy debate his identity for surely these aspects of Chicano culture did not pertain to the Anglo’s legacy.

The novel is a potpourri of story telling. Anaya spins no less than seventy-seven lessons on life and thirty-five myths, crafted by from what may be presumed were he author’s own hard earned experiences. Ever the master storyteller, Anaya uses the burning and then re-building of a bridge called The Bridge of Life, as a metaphor for mending the discrepancy that has been created between Mexican Immigrants who travel al Norte looking for work and the proverbial better life and their Americano/gringo counterparts. Randy must build this bridge across The River of Life to be reunited with his true love. Right after Randy resists the final temptation of el Diablo to go back to the land of the living, towards the end of the novel, there is a heart felt scene when the bridge, freshly built by mejicano the workers yell, “!Viva México! !Vivan los gringos!” It is a meant perhaps to be symbolic cheer, a genuine gesture of the desire of mejicanos to come to the United States, of their willingness to incorporate their customs with those of the gringo, to blend the two cultures and hopefully, evolve into americanos themselves. Randy tells them “’You have to learn English, customs, history, movies, music, so much.’ ‘We can do it!’ they cried.”

In response to his collection of short stories, The Man Who Could Fly and Other Stories,Tony Hillerman wrote of Rodolfo Anaya that he is the “godfather and guru of Chicano literature.” In this humble reader’s opnion it is la verdad. In Randy Lopez Goes HomeAnaya has created a story that teaches us the importance of reading the classics, confronts questions of Chicano identity, and shows aspiring writers the necessity to create fresh mythologies to convey modern life’s lessons. He calls for the future generations of Chicanos to reconcile their mestizo heritage and to rejoice in it. In the ‘Notes,’ Anaya states, “that is the lesson of Randy’s odyssey, the message from Agua Bendita, the strength and faith Patricia gave us. We learned we must renew our purpose daily. We must bless all of life.” While it is considered a Young Adult novel, this story will touch many grown up readers as they peel back its layers like the sweet maize from the husk during the harvest time of Anaya’s beloved homeland. —Marcelo Castillo has been an ongoing contributor to La Tolteca

2 Comments

Christina Gallegos July 03, 2020 - 17:47

I saw myself, I smelled the sweet aromas in my memo6ties. He validated my existence.

When I reached out to show “BlessMe Ultima” as a fundraiser for the Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area, he didn’t waver. When I told him the gabacho owned movie theater would not show it, he was delighted to assist. RIP maestro.

Ana Castillo July 06, 2020 - 16:34 – In reply to: Christina Gallegos

qepd